Using Museum Specimens to Learn About Harbor Seal’s Role in the Environment

Harbor seals are protected by the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA). At the same time, they are believed to be a significant predator of threatened Chinook salmon and could be competing with endangered southern resident killer whales. This poses a challenging management trade-off and data describing harbor seal’s historic impact on our food web, which would help guide this trade-off, is limited. By using old bone specimens stored at local museums and the scientific methods, researchers at University of Washington are uncovering more information.

Harbor seals experienced exponential growth in Puget Sound following the implementation of the MMPA, from historic lows of approximately 2,100 in 1972 before leveling off at the current population size of 18,000 (Jeffries et al. 2003). This change in predator abundance has been correlated to declines in forage fish and salmonid survival across the WA coast, which suggests harbor seals pose a threat to the recovery of endangered and vulnerable species in the region, including Chinook salmon and southern resident killer whales (Thomas et al. 2017).

However, this change in predator abundance also coincided with a broad-scale environmental regime shift known as the Pacific Decadal Oscillation in 1977/78, a phenomenon that has also been linked to productivity of fish species in WA, including salmon. Teasing apart these ecological drivers is challenging yet important for management of the Sound as an integrated system.

At the University of Washington, members of the Holtgrieve Ecosystem Ecology Lab, led by gradate student Megan Feddern, are trying to better understand the interactions between harbor seals, their prey and environmental changes to better inform management decisions from an ecosystem-based approach. They aim to do this by:

- Creating a dataset of where harbor seals have been feeding in the coastal WA food web over the past 100 years from museum skull specimens.

- Combine this dataset with other historic datasets of environmental drivers (Pacific Decadal Oscillation, El Niño Southern Oscillation, sea surface temperature) and important harbor seal prey species (herring biomass, salmon populations, Pacific Hake biomass) to identify what ecological components drive harbor seal food web position.

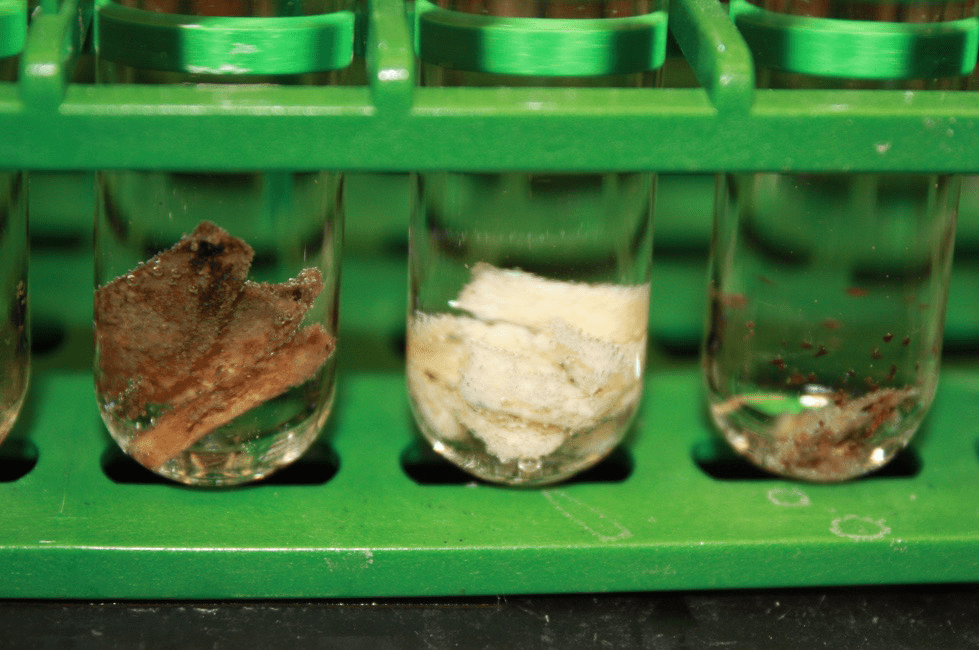

The research is made possible using a recent methodological advancement called compound specific stable isotope analysis of amino acids. Scientists are able to measure the nitrogen isotope ratio (15N/14N) of eleven different amino acids preserved in bone collagen. A small piece of bone (50 mg) is decalcified to access preserved collagen and measure the 15N/14N of the amino acids contained within that collagen and calculate the food web position of the harbor seal that collagen came from. Certain amino acids, called trophic amino acids, show an increase in 15N relative to 14N as an animal feeds higher in the food web. In other words, they’re able to get a better idea whether seals are eating, for instance, more herring or salmon.

During the study, 150 museum harbor seal skull specimens from seals from 1920-2017 have been obtained and the 15N/14N of their collagen has been measured. Scientists now have estimates of harbor seal food web position from the Hood Canal and Puget Sound during that time period, which they are currently comparing to data sets describing different environmental drivers.

Stay tuned for the full results!

This article was created using a flyer from the University of Washington. View it here.